Common causes of SQL Server Timeout

During a recent production run, a stored procedure timed out at peak order processing. This caused delays in processing orders and highlighted the importance of query performance in SQL Server environments.

We were able to resolve the timeout by updating the statistics on the critical tables. This experience provided valuable insights into why SQL Server queries can time out, how to troubleshoot them effectively, and, most importantly, how to prevent similar issues in the future.

The goal of this blog is to share those lessons. Whether you are a DBA, developer, or simply responsible for ensuring queries run reliably, this post will guide you through why SQL Server timeouts happen, how to analyze them, and best practices to maintain consistent performance.

Common causes of SQL Server Timeout.

- Long-Running Queries

- Blocking

- Deadlocks

Long-Running Queries

Long-running queries are one of the most common reasons for SQL Server timeouts. As data volume grows, queries that once performed well can slowly degrade, especially when indexes are missing or outdated.

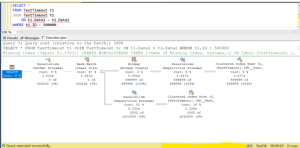

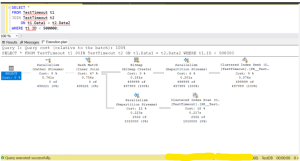

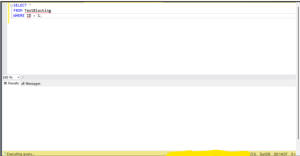

In our demo, we intentionally ran a query against a large table without proper indexing. The query performed a heavy join and scanned a significant number of rows, causing it to run for an extended period. When executed during peak usage, this type of query can easily exceed the application’s command timeout and fail.

Query ran with Include Actual Execution Plan

To analyze the issue, we monitored the running session using sys.dm_exec_requests the execution plan revealed a missing index.

Resolution:

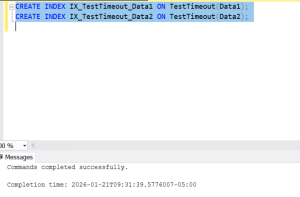

After creating the missing index, the query execution time dropped . This demonstrated how proper indexing can eliminate unnecessary work and prevent timeouts.

While missing indexes are a common cause of long-running queries, they are rarely the only factor. Outdated or Incorrect Statistics, Parameter Sniffing Poor Query Design, Non-SARGable Predicates, Excessive Data Processing, TempDB Pressure, Memory Grants and Spills, Lock Escalation, Hardware or Resource Pressure, Execution Plan Reuse Issues all play a critical role in query performance.

Blocking

Blocking occurs when one transaction holds locks on data that another transaction needs. While blocking itself is normal in SQL Server, problems arise when locks are held for too long.

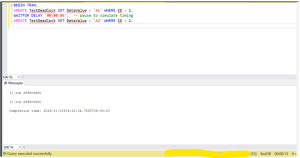

In our blocking simulation, Session 1 started a transaction and updated rows without committing or rolling back. This caused SQL Server to hold locks on those rows. When Session 2 attempted to read the same data, it was forced to wait.

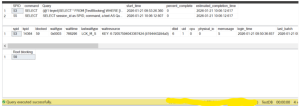

Using sys.dm_exec_requests, we could clearly identify the blocked session and the blocking session. As the wait time increased, the blocked query became a candidate for a timeout at the application level.

We have used below queries to get the blocking information.

SELECT session_id as SPID, command, a.text AS Query, start_time, percent_complete, dateadd(second,estimated_completion_time/1000, getdate()) as estimated_completion_time FROM sys.dm_exec_requests r CROSS APPLY sys.dm_exec_sql_text(r.sql_handle) a

select * from sys.sysprocesses where blocked<>0

select blocked as ‘Root blocking’ from sys.sysprocesses where blocked <> 0 except select spid from sys.sysprocesses where blocked <> 0

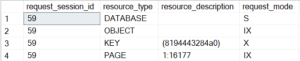

The output of sys.dm_tran_locks (Below query) helps determine whether a session is truly blocking others, the scope of its impact, and the appropriate response. By analyzing the resource type and lock mode, we can decide whether to wait, tune the query, or intervene.

SELECT

request_session_id,

resource_type,

resource_description,

request_mode

FROM sys.dm_tran_locks

WHERE request_session_id = 59;

Below result shows all locks currently held by session 59. SQL Server often takes multiple locks at different levels for a single operation

- DATABASE — Shared (S) Lock – Session 59 has a shared lock on the database. This is normal and indicates that the session is actively using the database.

- OBJECT — Intent Exclusive (IX) Lock – SQL Server plans to take exclusive locks at a lower level (rows or pages). IX locks signal intent, not actual data blocking yet.

- KEY — Exclusive (X) Lock – This is the most important row for blocking. Session 59 holds an exclusive lock on an index key. Any other session trying to read or update this same key will be blocked.

- PAGE — Intent Exclusive (IX) Lock – SQL Server intends to modify rows on this page. This supports the exclusive key lock above.

This output from sys.dm_tran_locks shows the locks held by the blocking session. The exclusive (X) lock on a KEY resource is the primary cause of blocking. As long as the transaction remains open, SQL Server will not release these locks, forcing other sessions to wait and potentially time out.

If session 59 holds many KEY or PAGE locks, it often means: Table scan, Large update, Missing index — We should make a decision to tune the query.

If locks move from: KEY → PAGE → OBJECT, That is a lock escalation. This indicates: Large batch operations, Poor batching strategy. — Break work into smaller batches, Commit more frequently.

When we need to consider killing the session ?

If Business impact is high, Session is idle or stuck, Blocking critical workloads, No application owner response.

Note : Kill <Spid> – Never the first option.

Resolution:

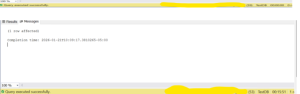

Once we committed or rolled back the transaction in Session 1, the locks were released immediately. Session 2 resumed execution and completed successfully.

Blocking is rarely caused by a single uncommitted transaction. Long-running transactions, poor indexing, isolation levels, lock escalation, and application design all contribute to blocking behavior. Identifying and addressing these root causes is essential to maintaining a healthy and responsive SQL Server environment.

Deadlocks

Deadlocks occur when two sessions block each other while waiting for resources, creating a cycle that cannot be resolved automatically. Unlike blocking, deadlocks are detected by SQL Server itself.

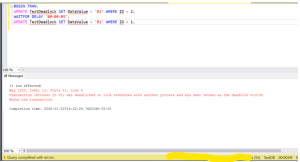

In our demo, two sessions attempted to update the same data in a different order. Each session held a lock that the other needed, creating a deadlock situation. SQL Server detected this condition and terminated one of the sessions as the deadlock victim.

We captured the deadlock information using the Extended Events session, which provides valuable insight into the queries and resources involved.

Create a Extended Event for Deadlock

CREATE EVENT SESSION [DeadlockMonitor] ON SERVER

ADD EVENT sqlserver.xml_deadlock_report

ADD TARGET package0.event_file(SET filename=N’C:\Deadlocks\DeadlockMonitor.xel’,max_file_size=(50))

WITH (MAX_MEMORY=4096 KB,EVENT_RETENTION_MODE=ALLOW_SINGLE_EVENT_LOSS,MAX_DISPATCH_LATENCY=30 SECONDS,MAX_EVENT_SIZE=0 KB,MEMORY_PARTITION_MODE=NONE,TRACK_CAUSALITY=OFF,STARTUP_STATE=OFF)

GO

![]()

View the Deadlock events with below query:

SELECT

EventXML.value(‘(event/@timestamp)[1]’, ‘DATETIME2’) AS DeadlockTime,

EventXML.query(‘(event/data/value)[1]’) AS DeadlockGraph

FROM

(

SELECT CAST(event_data AS XML) AS EventXML

FROM sys.fn_xe_file_target_read_file

(

‘C:\DeadLocks\DeadlockMonitor*.xel’,

NULL,

NULL,

NULL

)

WHERE object_name = ‘xml_deadlock_report’

) d;

A deadlock chain occurs when two or more sessions form a cycle of mutually blocking locks. SQL Server resolves it by terminating one session (the deadlock victim), but preventing chains requires consistent access patterns, short transactions, and proper indexing. Detecting the chain helps pinpoint the root cause of recurring deadlocks.

Resolution:

When SQL Server detects a deadlock, it automatically chooses one transaction as the deadlock victim and terminates it. Other transactions proceed once the conflicting locks are released. Unlike simple blocking, deadlocks indicate a design-level conflict that needs to be addressed to prevent recurrence.

Common Causes:

- Transactions accessing the same tables in different orders

- Long-running transactions holding locks too long

- Large batch operations without batching

- Missing or inefficient indexes causing scans and extensive locks

- High isolation levels (SERIALIZABLE, REPEATABLE READ)

- Application patterns holding locks while waiting for user input or multiple operations